Sunday, January 31, 2010

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Friday, January 29, 2010

Assaulting Arendt

A critique of criticism by Irving Horowitz in First Things magazine using an allegedly unfair assault on Hanna Arendt as a case in point:

The honorable tradition of criticism carries with it a displeasing aspect. This is especially the case in the higher academic circles. Reputations are too frequently made when pygmies stand on the shoulders of giants and when iconic and sometimes heroic figures are symbolically cut down to size. The theory is that, if the critic saws off the legs of those who have managed to stand tall for generations, the midgets can win handily in face-to-face combat with the dead. This is not to deny that even the most talented are sometimes in error; criticism is a useful art. It is, however, a derivative art. Criticism finds acceptance in a culture that measures success by small errors rather than by large-scale successes.

The recent critique of Hannah Arendt is a case in point. The most comprehensive assault to date, some thirty-five years after her death, is also the most recent. Bernard Wasserstein, professor of modern European Jewish history at the University of Chicago, comments on Arendt in the Times Literary Supplement in October 2009 under the title “Blame the Victim: Hannah Arendt Among the Nazis.” He offers not just a selective summary of “the historian and her sources” but also an umbrella of charges and allegations from other prominent figures over the past half century. One of the most infamous is that of my good friend Walter Laqueur—a significant figure in his own right. Wasserstein spares us the need to pick through the emotive rubble that has plagued Arendt’s career, stitching together a picture of her as either a gullible reader of neo-Nazi literature or a closet Jewish anti-Semite in need of intellectual detoxification.

After reading, reviewing, and writing on Hannah Arendt, I have come to think of her, fairly or otherwise, as a special voice, one of many—they range from Thomas Mann to Karl Jaspers to Marlene Dietrich—who came through the fires of hell called Nazi Germany with their consciences intact. An entire people was mesmerized by the rupture of a culture and a tradition that were entitled to be called the best in Western civilization but that ended up as the worst ever in Western civilization. The German nation began as a metaphor of Schiller’s ode to the spirit of human freedom and concluded with Hitler’s spirit of life taking on a scale of unparalleled horror.

March of the Peacocks

Paul Krugman of The New York Times has some doom and gloom to share with us on the real state of the union:

Last week, the Center for American Progress, a think tank with close ties to the Obama administration, published an acerbic essay about the difference between true deficit hawks and showy “deficit peacocks.” You can identify deficit peacocks, readers were told, by the way they pretend that our budget problems can be solved with gimmicks like a temporary freeze in nondefense discretionary spending.

One week later, in the State of the Union address, President Obama proposed a temporary freeze in nondefense discretionary spending.

Wait, it gets worse. To justify the freeze, Mr. Obama used language that was almost identical to widely ridiculed remarks early last year by John Boehner, the House minority leader. Boehner then: “American families are tightening their belt, but they don’t see government tightening its belt.” Obama now: “Families across the country are tightening their belts and making tough decisions. The federal government should do the same.”

What’s going on here? The answer, presumably, is that Mr. Obama’s advisers believed he could score some political points by doing the deficit-peacock strut. I think they were wrong, that he did himself more harm than good. Either way, however, the fact that anyone thought such a dumb policy idea was politically smart is bad news because it’s an indication of the extent to which we’re failing to come to grips with our economic and fiscal problems.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

Replacing evil

Based on his State of the Union speech last night, president Obama is showing little enthusiasm for confronting the Iranian nuclear threat. The best strategy to fight the regime? Robert Kagan of The Washington Post says: replace it.

Regime change in Tehran is the best nonproliferation policy. Even if the next Iranian government refused to give up the weapons program, its need for Western economic assistance and its desire for reintegration into the global economy and international order would at least cause it to slow today's mad rush to completion and be much more open to diplomatic discussion. A new government might shelve the program for a while, or abandon it altogether. Other nations have done so. In any event, an Iran not run by radicals with millennial visions would be a much less frightening prospect, even with a nuclear weapon.

The clinching argument is pragmatic. What is more likely: that Iran's present leadership will agree to give up its nuclear program, or that these leaders will be toppled? A year ago, the answer seemed obvious. There was little sign the Iranian people would ever rise up and demand change, no matter what the United States and other democratic nations did to help them. If the prospects for a deal on Tehran's nuclear program seemed remote, the prospects for regime change were even more remote.

These probabilities have shifted since June 12. Now the odds of regime change are higher than the odds the present regime will ever agree to give up its nuclear program. With tougher sanctions, public support from Obama and other Western leaders, and programs to provide information and better communications to reformers, the possibility for change in Iran may never be better. As Richard Haass wrote recently, "Even a realist should recognize that it's an opportunity not to be missed."

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

Who is he?

It's easy to find articles from the center or the right criticizing President Obama's performance. It's not so easy, however, to find an assault on his credibility from a trusted icon of the liberal left, like Bob Herbert of The New York Times:

Now with his poll numbers down and the Democrats’ filibuster-proof margin in the Senate about to vanish, Mr. Obama is trying again to position himself as a champion of the middle class. Suddenly, with the public appalled at the scandalous way the health care legislation was put together, and with Democrats facing a possible debacle in the fall, Mr. Obama is back in campaign mode. Every other utterance is about “fighting” for the middle class, “fighting” for jobs, “fighting” against the big bad banks.

The president who has been aloof and remote and a pushover for the health insurance and pharmaceutical industries, who has been locked in the troubling embrace of the Geithners and Summers and Ben Bernankes of the world, all of a sudden is a man of the people. But even as he is promising to fight for jobs, a very expensive proposition, he’s proposing a spending freeze that can only hurt job-creating efforts.

Mr. Obama will deliver his State of the Union address Wednesday night. The word is that he will offer some small bore assistance to the middle class. But more important than the content of this speech will be whether the president really means what he says. Americans want to know what he stands for, where his line in the sand is, what he’ll really fight for, and where he wants to lead this nation.

They want to know who their president really is.

Monday, January 25, 2010

Bigger Brother

A cogent analysis from The Economist on the "growl of hostility" we are witnessing to the rising power of the state:

IN THE aftermath of the Senate election in Massachusetts, the focus of attention is inevitably on what it means for Barack Obama. The impact on the Democratic president of the loss of the late Ted Kennedy’s seat to the Republicans will, no doubt, be significant. Yet the result could be remembered as a message more profound than the disparate mutterings of a grumpy electorate that has lost faith in its leader—as a growl of hostility to the rising power of the state.

America’s most vibrant political force at the moment is the anti-tax tea-party movement. Even in leftish Massachusetts people are worried that Mr Obama’s spending splurge, notably his still-unpassed health-care bill, will send the deficit soaring. In Britain, where elections are usually spending competitions, the contest this year will be fought about where to cut. Even in regions as historically statist as Scandinavia and southern Europe debates are beginning to emerge about the size and effectiveness of government.

There are good reasons, as well as bad ones, why the state is growing; but the trend must be reversed. Doing so will prove exceedingly hard—not least because the bigger and more powerful the state gets, the more it tends to grow. But electorates, as in Massachusetts, eventually revolt; and such expressions of voters’ fury are likely to shape politics in the years to come.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

A compassion gene?

In The Greater Good magazine, a report on new studies showing that compassion might just be part of the human DNA:

Humans are selfish. It's so easy to say. The same goes for so many assertions that follow. Greed is good. Altruism is an illusion. Cooperation is for suckers. Competition is natural, war inevitable. The bad in human nature is stronger than the good.

These kinds of claims reflect age-old assumptions about emotion. For millennia, we have regarded the emotions as the fount of irrationality, baseness, and sin. The idea of the seven deadly sins takes our destructive passions for granted. Plato compared the human soul to a chariot: the intellect is the driver and the emotions are the horses. Life is a continual struggle to keep the emotions under control.

Even compassion, the concern we feel for another being's welfare, has been treated with downright derision. Kant saw it as a weak and misguided sentiment: "Such benevolence is called soft-heartedness and should not occur at all among human beings," he said of compassion. Many question whether true compassion exists at all—or whether it is inherently motivated by self-interest.

Recent studies of compassion argue persuasively for a different take on human nature, one that rejects the preeminence of self-interest. These studies support a view of the emotions as rational, functional, and adaptive—a view which has its origins in Darwin's Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals. Compassion and benevolence, this research suggests, are an evolved part of human nature, rooted in our brain and biology, and ready to be cultivated for the greater good

Rescue minus

Ben Ehrenreich in Slate analyzes America's response to the Haitian humanitarian disaster:

"Command and control" turned out to be the key words. The U.S. military did what the U.S. military does. Like a slow-witted, fearful giant, it built a wall around itself, commandeering the Port-au-Prince airport and constructing a mini-Green Zone. As thousands of tons of desperately needed food, water, and medical supplies piled up behind the airport fences—and thousands of corpses piled up outside them—Defense Secretary Robert Gates ruled out the possibility of using American aircraft to airdrop supplies: "An airdrop is simply going to lead to riots," he said. The military's first priority was to build a "structure for distribution" and "to provide security." (Four days and many deaths later, the United States began airdropping aid.)

The TV networks and major papers gamely played along. Forget hunger, dehydration, gangrene, septicemia—the real concern was "the security situation," the possibility of chaos, violence, looting. Never mind that the overwhelming majority of on-the-ground accounts from people who did not have to answer to editors described Haitians taking care of one another, digging through rubble with their bare hands, caring for injured loved ones—and strangers—in the absence of outside help. Even the evidence of "looting" documented something that looked more like mutual aid: The photograph that accompanied a Sunday New York Times article reporting "pockets of violence and anarchy" showed men standing atop the ruins of a store, tossing supplies to the gathered crowd.

The guiding assumption, though, was that Haitian society was on the very edge of dissolving into savagery. Suffering from "progress-resistant cultural influences" (that's David Brooks finding a polite way to call black people primitive), Haitians were expected to devour one another and, like wounded dogs, to snap at the hands that fed them. As much as any logistical bottleneck, the mania for security slowed the distribution of aid.

Air-traffic control in the Haitian capital was outsourced to an Air Force base in Florida, which, not surprisingly, gave priority to its own pilots. While the military flew in troops and equipment, planes bearing supplies for the Red Cross, the World Food Program, and Doctors Without Borders were rerouted to Santo Domingo in neighboring Dominican Republic. Aid flights from Mexico, Russia, and France were refused permission to land. On Monday, the British Daily Telegraph reported, the French minister in charge of humanitarian aid admitted he had been involved in a "scuffle" with a U.S. commander in the airport's control tower. According to the Telegraph, it took the intervention of the United Nations for the United States to agree to prioritize humanitarian flights over military deliveries.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Friday, January 22, 2010

Are you a looter?

Would you loot a supermarket to feed your starving kids, if you had no choice? So would I. Rebecca Solnit from the magazine Guernica:

Soon after almost every disaster the crimes begin: ruthless, selfish, indifferent to human suffering, and generating far more suffering. The perpetrators go unpunished and live to commit further crimes against humanity. They care less for human life than for property. They act without regard for consequences.

I’m talking, of course, about those members of the mass media whose misrepresentation of what goes on in disaster often abets and justifies a second wave of disaster. I’m talking about the treatment of sufferers as criminals, both on the ground and in the news, and the endorsement of a shift of resources from rescue to property patrol. They still have blood on their hands from Hurricane Katrina, and they are staining themselves anew in Haiti.

Within days of the Haitian earthquake, for example, the Los Angeles Times ran a series of photographs with captions that kept deploying the word “looting.” One was of a man lying face down on the ground with this caption: “A Haitian police officer ties up a suspected looter who was carrying a bag of evaporated milk.” The man’s sweaty face looks up at the camera, beseeching, anguished.

Another photo was labeled: “Looting continued in Haiti on the third day after the earthquake, although there were more police in downtown Port-au-Prince.” It showed a somber crowd wandering amid shattered piles of concrete in a landscape where, visibly, there could be little worth taking anyway.

A third image was captioned: “A looter makes off with rolls of fabric from an earthquake-wrecked store.” Yet another: “The body of a police officer lies in a Port-au-Prince street. He was accidentally shot by fellow police who mistook him for a looter.”

People were then still trapped alive in the rubble. A translator for Australian TV dug out a toddler who’d survived 68 hours without food or water, orphaned but claimed by an uncle who had lost his pregnant wife. Others were hideously wounded and awaiting medical attention that wasn’t arriving. Hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, needed, and still need, water, food, shelter, and first aid. The media in disaster bifurcates. Some step out of their usual “objective” roles to respond with kindness and practical aid. Others bring out the arsenal of clichés and pernicious myths and begin to assault the survivors all over again.

The “looter” in the first photo might well have been taking that milk to starving children and babies, but for the news media that wasn’t the most urgent problem. The “looter” stooped under the weight of two big bolts of fabric might well have been bringing it to now homeless people trying to shelter from a fierce tropical sun under improvised tents.

The pictures do convey desperation, but they don’t convey crime. Except perhaps for that shooting of a fellow police officer—his colleagues were so focused on property that they were reckless when it came to human life, and a man died for no good reason in a landscape already saturated with death.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Reading others

From The Smart Set, an essay on cultural insularity-- it's not just an American tradition:

It is impossible to write about such a book as Best European Fiction 2010 without also writing about America's disinterest in such a book. Neither Zadie Smith nor Aleksandar Hemon could do it — and they're the author of the introduction and the editor of the anthology. It's a well worn angle by now: the fact that only three percent of literature published in the U.S. is work of translation, the fact that most of that work is being published by small independent presses and university presses. How else to explain how this anthology came to being in a place called Normal, Illinois from a small press named Dalkey Archive, its very name being an obscure Irish literature reference. Rather than from, say, Harcourt Houghton Mifflin, which produces almost identical anthologies of every other subject in the world: travel writing, sports writing, short stories, essays, whatever the hell that McSweeneys one is. Nonrequired Reading? Comic books, sure, they're all over that. But literature written in another language? God. We're not running a charity here.

We should also probably talk about the Nobel. It's our annual dose of international literature, the one time of year there's a rush on a writer from Romania or France or Hungary. Ever since the head of the Nobel literature committee, Horace Engdahl, said that American culture is too "insular," Americans have had issues with the Nobel. Who am I kidding — we have had issues way before then. Mr. Nobel made a true statement, but not a profound one. It presupposes that other cultures are not insular. Are the Nigerians really that interested in the literature coming out of Denmark? The Latvians in Phillipean poetry? No. Each culture is primarily interested in its own subject, plus whatever is coming out of America. With that arithmetic, we are even with everyone else. We just don't have a market larger than our own to aspire to. We'll occasionally look to Britain, mostly as something to simultaneously aspire to and rebel against, sort of like our father — but for the most part, we honestly believe we are making the great contributions to culture.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Obama: Two views

Two opposing views on the Scott Brown victory in Massachussets last night: Victor Davis Hanson at National Review sees dark days ahead for the Obama administration, while Jonathan Cohn at The New Republic calls for "full speed ahead" on health care reform. Both pieces are logical and very well written. You decide.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Muslim sham?

Behind recent reports of Muslim cooperation in the war against radical Islam is a more sobering story, as reported today in The New York Post:

The Anti-Defamation League last week said new efforts by American Muslim groups "to root out radicalization" were "a sham." As an example, it pointed to a Chicago convention staged by the Muslim American Society and the Islamic Circle of North America last month -- which, ADL National Director Abe Foxman said, was "nothing more than a cover for the dissemination of hateful anti-American and anti-Israel views and anti-Semitism."

Participants accused America of attacking Islam and targeting US Muslims at home and abroad. On sale, ADL reported, were books and CDs by such firebrands as Anwar al-Awlaki -- the Muslim cleric linked to al Qaeda.

The ADL's not alone. Another law-enforcement source tells me CAIR and other groups have been worse than useless: To this source's knowledge, US Muslims have played virtually no role in foiling local plots.

Indeed, in some places, imams have reportedly withheld useful info and threatened to oust congregants who aid law-enforcement. Officials say Ahmad Afzali, the Queens imam helping agents probe Najibullah Zazi (the coffee vendor charged in a New York terror plot), later double-crossed them and alerted Zazi.

"I know of no investigations" in which Muslims have been helpful, Rep. Peter King (R-LI), the ranking member of the House Homeland Security Committee, tells me. He says law-enforcement and counterterror officials invariably tell him Muslim cooperation doesn't exist. Sometimes agents say they're met with hostility.

For folks who "understand the nature of the threat" and watch officials from "CAIR and the Muslim Public Affairs Council on major [TV] networks, it's incredibly demoralizing," a former FBI special agent says.

A reluctance to even acknowledge pro-terrorist sympathies persists even beyond official Muslim groups. At universities, for example, Muslim students have blocked speeches by people like Nonie Darwish -- an anti-terror activist who calls herself a "former Muslim" and who speaks about the Islamic links to terror. In the last two months, scheduled Darwish talks at Princeton and Columbia were canceled at the last minute, after Muslim objections. At Boston University, someone lit a fire in a building where she was to speak.

Monday, January 18, 2010

The roots of Obama worship

A provocative essay by James Ceaser in The Weekly Standard on the tension between Obama's dual role as leader of America and leader of the Religion of Humanity:

In what measure has Barack Obama as president embraced this other role of leader of Humanity? Americans are now wondering. These concerns first came to light in unsympathetic reactions to Obama’s foreign policy speeches, especially those delivered on foreign soil, that made a point of apologizing for American missteps and wrongs. Realists and pragmatists dismissed these criticisms, arguing that the new approach served America’s interests by lowering the strident tone of the Bush years, thereby opening doors to engagement with other leaders and defusing anti-Americanism. In addition, it was said that Obama could leverage his position as a leader of humanity to help solve general problems like nuclear proliferation and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Obama’s two offices complemented one another, promoting the goals of Humanity while serving America’s interest. By standing above or outside America, he could best help America.

Whatever the plausibility of these arguments, their merit over the past year has been tested and found wanting. Obama’s authority as leader of Humanity has not borne the fruit that many had hoped for, and in any case—as his two trips to Copenhagen have made clear—his standing in the world is now in a free fall. Americans who thought that it is one thing to offer an initial hand to the likes of a Chávez or an Ahmadinejad think it something quite different to continue to offer it after the hand has been flagrantly rejected. To persist is to invite dishonor, both for the office of the president and for the nation. Realism dictates an adjustment. The fact that such a change has been so slow in coming suggests that it is not realism that is Obama’s guiding light, but a commitment to the dogmas of the Religion of Humanity.

Another instance of the conflict Americans now perceive between the two roles comes in the form of Obama’s repeated efforts to blame George W. Bush (or “the last eight years”) for every difficulty or problem that the nation confronts. On first encounter, there would seem to be nothing more in this tactic than an ordinary political calculation designed to win support and deflect criticism. But this technique, which is standard fare for a presidential campaign, at a certain point is bound to appear unpresidential, not only when indulged in before foreign audiences where it seeks to purchase a personal reputation for impartiality at the expense of national unity, but also in domestic affairs. It displays weakness by evidencing a desire to evade responsibility, especially for a president who based his Inaugural Address on calling for “a new era of responsibility.” Opinions may differ on whether the “blame Bush first” policy is obsessive or demagogic, but it is by now clear that it is counterproductive. Persistence bespeaks something more than political miscalculation. For the Religion of Humanity, the attack on Bush, both the man and the “substance,” is a matter of dogma. If Obama were to desist, he would relinquish his higher office.

The same pressure to hew to the dictates of the new religion is evident in the efforts of Obama’s intellectual supporters to save postpartisanship from the simple hoax that most now believe it to have been. Postpartisanship, we are told, never meant anything as mundane as dealing with the other party. It referred instead to working with those who embrace the consensus of the new era. It therefore explicitly excludes the bulk of the Republican party, which comprises those who cling stubbornly to their theology and metaphysics. Only those elements that have adapted or evolved qualify as potential postpartisan partners. The standard for inclusion is not an expression of popular will, but criteria supplied by the idea of progress. What has made many Americans increasingly suspicious of the office of leader of Humanity is their growing perception that it rests ultimately on contempt for the people.

The conflicting demands of the Religion of Humanity and the presidency of the United States have become most apparent in the administration’s approach to dealing with the threat of Islamic terrorism. The Religion of Humanity, by its own reckoning, admits to facing challenges from two quarters: from those who have not yet fully entered the age of Positivism, which includes the terrorists, and from those who are part of the advanced world but who refuse to embrace it, which includes the likes of George W. Bush. In the present situation, these two groups are understood to have a symbiotic relationship. The existence of the terrorists is regrettable, not only because of the physical threat that they pose, but also because, by doing so, they risk strengthening the hand of those in the West who reject the Religion of Humanity. Supporters of the Religion of Humanity therefore believe they have good reason to deny or minimize the danger of terrorism in order to save the world from the even greater danger of the triumph of the retrograde forces. This is the dogmatic basis of political correctness, and Obama and his team have gone to considerable lengths by their policies and by their use of language to hide reality. But reality has a way of asserting itself, and it is becoming clearer by the day that being the leader of Humanity is incompatible with being the president of the United States. No man can serve two masters.

Sunday, January 17, 2010

The second language

A meditation on English as a second language from The American Scholar:

So what is good English—the language we’re here today to wrestle with? It’s not as musical as Spanish, or Italian, or French, or as ornamental as Arabic, or as vibrant as some of your native languages. But I’m hopelessly in love with English because it’s plain and it’s strong. It has a huge vocabulary of words that have precise shades of meaning; there’s no subject, however technical or complex, that can’t be made clear to any reader in good English—if it’s used right. Unfortunately, there are many ways of using it wrong. Those are the damaging habits I want to warn you about today.

First, a little history. The English language is derived from two main sources. One is Latin, the florid language of ancient Rome. The other is Anglo-Saxon, the plain languages of England and northern Europe. The words derived from Latin are the enemy—they will strangle and suffocate everything you write. The Anglo-Saxon words will set you free.

How do those Latin words do their strangling and suffocating? In general they are long, pompous nouns that end in -ion—like implementation and maximization and communication (five syllables long!)—or that end in -ent—like development and fulfillment. Those nouns express a vague concept or an abstract idea, not a specific action that we can picture—somebody doing something. Here’s a typical sentence: “Prior to the implementation of the financial enhancement.” That means “Before we fixed our money problems.”

Believe it or not, this is the language that people in authority in America routinely use—officials in government and business and education and social work and health care. They think those long Latin words make them sound important. It no longer rains in America; your TV weatherman will tell that you we’re experiencing a precipitation probability situation.

Friday, January 15, 2010

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Don't like the numbers? Change them!

In the search for power, nothing is safe, not even cold numbers-- as Michael Boskin reports in The Wall Street Journal:

Politicians and scientists who don't like what their data show lately have simply taken to changing the numbers. They believe that their end—socialism, global climate regulation, health-care legislation, repudiating debt commitments, la gloire française—justifies throwing out even minimum standards of accuracy. It appears that no numbers are immune: not GDP, not inflation, not budget, not job or cost estimates, and certainly not temperature. A CEO or CFO issuing such massaged numbers would land in jail.

The late economist Paul Samuelson called the national income accounts that measure real GDP and inflation "one of the greatest achievements of the twentieth century." Yet politicians from Europe to South America are now clamoring for alternatives that make them look better.

A commission appointed by French President Nicolas Sarkozy suggests heavily weighting "stability" indicators such as "security" and "equality" when calculating GDP. And voilà!—France outperforms the U.S., despite the fact that its per capita income is 30% lower. Nobel laureate Ed Prescott called this disparity the difference between "prosperity and depression" in a 2002 paper—and attributed it entirely to France's higher taxes.

With Venezuela in recession by conventional GDP measures, President Hugo Chávez declared the GDP to be a capitalist plot. He wants a new, socialist-friendly way to measure the economy. Maybe East Germans were better off than their cousins in the West when the Berlin Wall fell; starving North Koreans are really better off than their relatives in South Korea; the 300 million Chinese lifted out of abject poverty in the last three decades were better off under Mao; and all those Cubans risking their lives fleeing to Florida on dinky boats are loco.

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

No tortured soul

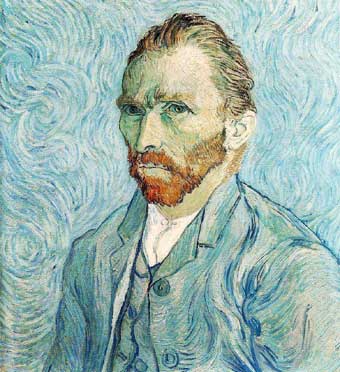

From the British magazine Standpoint, a different take on the artist Vincent Van Gogh-- on his sanity, his prolific output and his little-known love for the written word:

One learns time and again that both words and images fuelled Van Gogh's imagination equally. "Books and reality and art are the same kind of thing for me." And then, echoing this sentiment, "One has to learn to read, as one has to learn to see and learn to live."

Van Gogh was a voracious reader-fluent in Dutch, French and English. He read all of Dickens in English (Hard Times was his favourite), he was particularly moved by Shakespeare's history plays, and he loved Flaubert and Maupassant. Indeed, he was extremely knowledgeable about much of the French fiction of his day. In addition, he learned a great deal about Japan from the fiction of Pierre Loti, particularly his bestselling Madame Chrysanthème, the basis for Puccini's Madame Butterfly. Van Gogh identified particularly with French naturalist writers, and was inspired by Zola's depiction of Parisian life, reading all 20 novels in Zola's Rougon-Macquart cycle. "[They] paint life as we feel it ourselves, and thus satisfy that need which we have, that people tell the truth," he wrote to Wil in 1887.

Although Arles was once the capital of Gaul, in the western Roman Empire, Van Gogh was interested in none of its history. Instead, it was here that he wrote something of his mission statement to paint the here and now and the everyday. Unlike Gauguin, who declared that he sought only to paint his visions and his dreams, Van Gogh wanted to paint life as it was happening around him: "The zouaves, the brothels, the adorable little Arlesiennes going to their first communion...the priest in his surplice who looks like a dangerous rhinoceros, the absinthe drinkers..."

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Talking vs being

Talking about race might come across as insensitive, but it's not the same as racist talk, as Mary Mitchell explains in the Chicago Sun Times:

If it were not so pathetic, the political fallout over remarks made by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid would be hilarious.

Reid is under attack for saying privately in 2008 that then-Sen. Barack Obama would be a successful black presidential candidate because of his "light-skinned" appearance and because he doesn't speak with a "Negro dialect unless he wanted to have one."

Frankly, a lot of African Americans must have yawned.

Reid only confirmed what a lot of black voters thought -- which is why Obama wrestled with questions about "his blackness" throughout his campaign.

Indeed, the people who publicly raised concerns about Obama's "color" most often were not white. They were black.

For instance, during the heated primary between Obama and Hillary Clinton, former U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young said that former President Bill Clinton was "every bit as black as Obama."

The racially charged message was intended to warn African-American voters against embracing Obama out of black pride because he looked like one of them.

Reid also isn't the first white senator to give Obama a backhanded racial compliment.

Vice President Joe Biden's formal announcement that he was running for president was marred by comments he made about having to compete against Obama.

"You got the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy. I mean that's a storybook, man," Biden told a reporter with the New York Observer.

GOP smells blood

Reid has personally apologized to Obama about his comments, but his kowtowing isn't likely to be enough.

We are in a political environment where Republicans are desperately searching for a hammer they can use to smack down the Democratic agenda.

When used to describe Obama's attractiveness, the terms "light-skinned," "Negroes," and "dialect" are words loaded with negative energy.

Monday, January 11, 2010

Sunday, January 10, 2010

Reviving America

A long essay by James Fallows in The Atlantic on how America can rise again:

America will be better off if China does well than if it flounders. A prospering China will mean a bigger world economy with more opportunities and probably less turmoil—and a China likely to be more cooperative on environmental matters. But whatever happens to China, prospects could soon brighten for America. The American culture’s particular strengths could conceivably be about to assume new importance and give our economy new pep. International networks will matter more with each passing year. As the one truly universal nation, the United States continually refreshes its connections with the rest of the world—through languages, family, education, business—in a way no other nation does, or will. The countries that are comparably open—Canada, Australia—aren’t nearly as large; those whose economies are comparably large—Japan, unified Europe, eventually China or India—aren’t nearly as open. The simplest measure of whether a culture is dominant is whether outsiders want to be part of it. At the height of the British Empire, colonial subjects from the Raj to Malaya to the Caribbean modeled themselves in part on Englishmen: Nehru and Lee Kuan Yew went to Cambridge, Gandhi, to University College, London. Ho Chi Minh wrote in French for magazines in Paris. These days the world is full of businesspeople, bureaucrats, and scientists who have trained in the United States.

Today’s China attracts outsiders too, but in a particular way. Many go for business opportunities; or because of cultural fascination; or, as my wife and I did, to be on the scene where something truly exciting was under way. The Haidian area of Beijing, seat of its universities, is dotted with the faces of foreigners who have come to master the language and learn the system. But true immigrants? People who want their children and grandchildren to grow up within this system? Although I met many foreigners who hope to stay in China indefinitely, in three years I encountered only two people who aspired to citizenship in the People’s Republic. From the physical rigors of a badly polluted and still-developing country, to the constraints on free expression and dissent, to the likely ongoing mediocrity of a university system that emphasizes volume of output over independence or excellence of research, the realities of China heavily limit the appeal of becoming Chinese. Because of its scale and internal diversity, China (like India) is a more racially open society than, say, Japan or Korea. But China has come nowhere near the feats of absorption and opportunity that make up much of America’s story, and it is very difficult to imagine that it could do so—well, ever.

Saturday, January 9, 2010

Friday, January 8, 2010

Hero Israel

David Horovitz of The Jerusalem Post on how the pariah state Israel has suddenly become a world hero:

And so, reeling at the surrealism of it all, we watch talking heads in TV interviews, using the tones of patronizing academics addressing some very dull students, hammering home the point: You've got to do it the Israeli way. You just can't scan and triple-check everybody and shouldn't try to. You'll make air travel impossible and create massive lines at airports which would obviate the necessity for terrorists to get on board; they could just shoot up the airports. You have to use intelligence - intelligence in gathering information on potential threats, and intelligence in applying security measures at check-in.

Again and again in this new upside-down world where we, implausibly, are suddenly the smart guys, the mantra runs: Look at the Israelis. Their main international airport was shot up by the Japanese Red Army. Their planes were hijacked by Palestinian terror groups. And they wised up.

Protect your airports with outer rings of security, the global experts urge - like the Israelis do. Put air marshals on board your planes - like the Israelis do. Profile your passengers - like the Israelis do. And no, that's not racism, it's pragmatism. Yes, the Israelis emphatically do focus on Muslims; there's no denying the truism that while all Muslims are certainly not terrorists, most terrorists are Muslims. But ethnic origin is only one of the factors that rings the Hebrew alarms.

Israel's security apparatus, the experts point out in their newly tolerated admiration, looks at a host of other factors which, understandably, it doesn't talk too much about in public. But if you examine the way Anne Murphy was intercepted at Heathrow Airport in 1986, some have astutely pointed out, you start to get the idea. Here was a naïve pregnant Irish woman who had no idea that the bag her Jordanian fiancé had so kindly given her, to carry her personal belongings for their holiday in Israel, contained a false bottom filled with Semtex plastic explosives. She hadn't the faintest notion that, in the service of his Syrian state-intelligence paymasters, Nezar Hindawi was sending her and their unborn child to their deaths. And neither, until she reached El Al security, did Israeli intelligence.

But Murphy was traveling alone on a ticket that had been purchased only shortly before the flight. That would immediately have raised some red flags. The most rudimentary questioning would then have established that her Arab boyfriend had told her he was flying out separately and would meet her there. And from that point on, there was no way that Murphy and her incendiary bag were going any further without the most stringent checking and rechecking. The result: A bomb-plot foiled and hundreds of innocent lives saved. That's the way you safeguard air travel. The intelligent way. The Israeli way.

Flash forward 23 years. Abdulmutallab had purchased his ticket to the US with cash - a reported $2,831 to be precise, at the KLM office in Ghana, from where he traveled to Nigeria, the Netherlands and on toward the destination he intended to prevent his 288 fellow passengers and crew from reaching, Detroit. He had provided no contact address. He was traveling with no luggage. And it was a one-way ticket. Would Israeli-style security procedures have thwarted him long before he got near a plane, even without helpful warnings from his father and intercepted "chatter" about al-Qaida sending a Nigerian to blow up a flight heading into the US? I rather think so.

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Against cheerfulness

In Reason magazine, a review of Barbara Ehrenreich's new book, "Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America." Enjoy:

One of my earliest memories is no more than a command: “Smile.” The directive was delivered by my father, standing over me in a church pew, definitely not smiling. I wasn’t so much a morose kid as a deeply internal one, and whatever expression I made while lost in thought lacked the cheerfulness expected of little girls. As I would learn soon after that day in church, an American female with a downward-sloping mouth cannot escape the tyranny of smile-pushers. My dad’s request was echoed by teachers (“Try to look interested”), relatives (“Why so glum?”), and, much later, random construction workers (“Smile, baby!”).

So it’s more than a little refreshing to know that Barbara Ehrenreich doesn’t care whether you smile. Indeed, she’d rather you not. In Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America, she accuses positivity freaks of corrupting the media, infiltrating medical science, perverting religion, and destroying the economy. In her attempt to link starfish-shaped “reach for the stars” beanbags and global economic devastation, Ehrenreich gets ahead of herself, but along the way she pushes back against a kind of cultural pressure so totalizing we sometimes fail to notice its existence.

All the Oprah-ready gurus you would expect to populate this polemic show up to share some advice—here’s Joel Osteen warning us never to “verbalize a negative emotion,” there’s Tony Robbins exhorting us to “Get motivated!” In turning the United States into a 24-hour pep rally, charges Ehren-reich, these professional cheerleaders have all but drowned out downers like “realism” and “rationality.” Their followers are trained to dismiss bad news rather than assimilate or reflect upon its importance. Motivators counsel an upbeat ignorance—the kind of illusory worldview that might, say, convince a president that his soldiers will be greeted as liberators in a foreign state, or a mayor that his city’s crumbling levees can withstand the force of a hurricane.

But Ehrenreich seems less worried about what positivity fans value than what they ignore. Her idea of a life well-lived, as she repeatedly tells us, involves storming into the world and demanding progressive political change. Positivity’s decidedly inward focus—in which the solution to every problem lies in a mere attitudinal shift—thus seems troubling, a “retreat from the real drama and tragedy of human events.” When a Kansas City pastor declares his church “complaint-free,” Ehrenreich sees a demand that Americans content themselves with their dismal lot. When companies hire motivators to boost morale in the workplace, she sees “a means of social control” by which disgruntled employees are brainwashed into acquiescence. “America’s white-collar corporate work-force drank the Kool-Aid,” she writes, “and accepted positive thinking as a substitute for their former affluence and security.”

Wednesday, January 6, 2010

Theatrics vs safety

It's a fight to the finish. America's deep attachment to "treating everyone equally" vs. its responsibility to protect its citizens. Can both be done? We shall see. So far, the former is slightly ahead, as illustrated by the Mickey Mouse airport security measures that focus on things rather than people. This is quite different than the Israeli approach, as explained by Daniel Pipes in The Jerusalem Post:

HAD EL Al followed the usual Western security procedures, 375 lives would surely have been lost somewhere over Austria. The bombing plot came to light, in other words, through a nontechnical intervention relying on conversation, perception, common sense and (yes) profiling. The agent focused on the passenger, not the weaponry.

Israeli counterterrorism takes passengers' identities into account; accordingly, Arabs endure an especially tough inspection. "In Israel, security comes first," David Harris of the American Jewish Committee explains.

Obvious as this sounds, overconfidence, political correctness and legal liability render such an approach impossible anywhere else in the West. In the US, for example, one month after 9/11, the Department of Transportation issued guidelines forbidding its personnel from generalizing "about the propensity of members of any racial, ethnic, religious or national origin group to engage in unlawful activity." (Wear a hijab, I semi-jokingly advise women wanting to avoid secondary screening at airport security.)

WORSE YET, consider the panicky Mickey-Mouse steps the US Transportation Security Administration implemented hours after the Detroit bombing attempt: no crew announcements "concerning flight path or position over cities or landmarks," and disabling all passenger communications services. During a flight's final hour, passengers may not stand up, access carry-on baggage nor "have any blankets, pillows or personal belongings on the lap."

Some crews went yet further, keeping cabin lights on throughout the night while turning off the in-flight entertainment, prohibiting all electronic devices and, during the final hour, requiring passengers to keep hands visible and neither eat nor drink. Things got so bad, the Associated Press reports, "a demand by one attendant that no one could read anything... elicited gasps of disbelief and howls of laughter."

Widely criticized for these Clouseau-like measures, TSA eventually decided to add "enhanced screening" for travelers passing through or originating from 14 "countries of interest" - as though one's choice of departure airport indicates a propensity for suicide bombing.

The TSA engages in "security theater" - bumbling pretend-steps that treat all passengers equally rather than risk offending anyone by focusing, say, on religion. The alternative approach is Israelification, defined by The Toronto Star as "a system that protects life and limb without annoying you to death."

Which do we want - theatrics or safety?

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

Prehistoric geniuses?

Did big-brained human geniuses live many millennia ago? Discover magazine explores:

Perhaps the Boskops were trapped by their ability to see clearly where things would head. Perhaps they were prisoners of those majestic brains.

There is another, again poignant, possible explanation for the disappearance of the big-brained people. Maybe all that thoughtfulness was of no particular survival value in 10,000 B.C. The great genius of civilization is that it allows individuals to store memory and operating rules outside of their brains, in the world that surrounds them. The human brain is a sort of central processing unit operating on multiple memory disks, some stored in the head, some in the culture. Lacking the external hard drive of a literate society, the Boskops were unable to exploit the vast potential locked up in their expanded cortex. They were born just a few millennia too soon.

In any event, Boskops are gone, and the more we learn about them, the more we miss them. Their demise is likely to have been gradual. A big skull was not conducive to easy births, and thus a within-group pressure toward smaller heads was probably always present, as it still is in present-day humans, who have an unusually high infant mortality rate due to big-headed babies. This pressure, together with possible interbreeding with migrating groups of smaller-brained peoples, may have led to a gradual decrease in the frequency of the Boskop genes in the growing population of what is now South Africa.

Then again, as is all too evident, human history has often been a history of savagery. Genocide and oppression seem primitive, whereas modern institutions from schools to hospices seem enlightened. Surely, we like to think, our future portends more of the latter than the former. If learning and gentility are signs of civilization, perhaps our almost-big brains are straining against their residual atavism, struggling to expand. Perhaps the preternaturally civilized Boskops had no chance against our barbarous ancestors, but could be leaders of society if they were among us today.

Maybe traces of Boskops, and their unusual nature, linger on in isolated corners of the world. Physical anthropologists report that Boskop features still occasionally pop up in living populations of Bushmen, raising the possibility that the last of the race may have walked the dusty Transvaal in the not-too-distant past. Some genes stay around in a population, or mix themselves into surrounding populations via interbreeding. The genes may remain on the periphery, neither becoming widely fixed in the population at large nor being entirely eliminated from the gene pool.

Just about 100 miles from the original Boskop discovery site, further excavations were once carried out by Frederick FitzSimons. He knew what he had discovered and was eagerly seeking more of these skulls.

At his new dig site, FitzSimons came across a remarkable piece of construction. The site had been at one time a communal living center, perhaps tens of thousands of years ago. There were many collected rocks, leftover bones, and some casually interred skeletons of normal-looking humans. But to one side of the site, in a clearing, was a single, carefully constructed tomb, built for a single occupant—perhaps the tomb of a leader or of a revered wise man. His remains had been positioned to face the rising sun. In repose, he appeared unremarkable in every regard...except for a giant skull.

Review of '09

George Will's "Clunker of a Year" summary of 2009:

Tsutomu Yamaguchi, 93, was on a business trip in Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. Three days later he was back home in Nagasaki. He also survived 2009. Common sense did not. In Black History Month, a.k.a. February, pupils at a Burlington, N.J., public elementary school sang, "Hello Mr. President/We honor you today/For all your great accomplishments/We all do say 'Hooray!' " So did a smitten Nobel committee.

For peace, not economics. For $3 billion, Cash for Clunkers moved many car sales from September to August. By law, the clunkers had to be junked, which boosted used-car prices, penalizing low-income people. Having used stimulus money to give raises to its 317 employees, Head Start in Augusta, Ga., reported 317 jobs created. A Georgia nonprofit multiplied the percentage of raises (1.84) it gave by the number of employees receiving them (508) and reported the stimulus had saved 935 jobs. What was stimulated, aside from bookkeeping nonsense, was demand for Ayn Rand's novel Atlas Shrugged, a hymn to unfettered capitalism. Sales exceeded 400,000, double the total in any of the 52 years since it was published.

America's most portentous domestic event of 2009 was California's deepening crisis, which may prefigure the nation's trajectory. Abroad, Montblanc, the Swiss penmaker, with its eye on the potential buyers in India, commemorated Mahatma Gandhi with a $23,000 pen engraved with the ascetic's image. In the mall beneath the Louvre, culture mavens now can dine at a McDonald's. Brown University's faculty voted to rename Columbus Day "Fall Weekend," presumably to punish the explorer for spoiling the Western Hemisphere paradise where human sacrifices were still happening when he arrived. The Empire State Building was bathed in red and yellow light to honor the 60th anniversary of China's regime, which is responsible for more deaths than Hitler and Stalin combined.

In 2009 the two most important unelected policymakers in Washington were put in their offices by George W. Bush: Ben Bernanke, chairman of the Federal Reserve, and Defense Secretary Robert Gates. In December there were more U.S. troops deployed in the two wars than there were in January. Iran, threatened with economic sanctions, announced plans to sharply increase its uranium enrichment. "North Korea," said Barack Obama in December, "must live up to its obligations." Must?

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine blamed obesity for global warming: Each fat person supposedly adds an extra ton of carbon dioxide every year because of respiration, and because of the carbon costs of raising and transporting the extra food he or she devours. Alarmingly, global warming took a sabbatical for another year: A report in the journal Science argued that warming is necessary to prevent a descent into a new Ice Age.

There were more minority children than white children in one sixth of America's counties. A national survey revealed that the West Coast has been surpassed by New England—where the Puritans landed for their errand into the -wilderness—as the least religious region.

When the Olympic Committee voted against Chicago, Indiana's Gov. Mitch Daniels wondered, "What is the world coming to when Chicago can't fix an election?" Atlanta, which is 57 percent black, came within 714 votes (out of 84,384 cast) of electing a white mayor. Forty-five years after three civil-rights workers were murdered in Philadelphia, Miss., that town elected a black mayor.

In the glandular lives of the famous, South Carolina's Gov. Mark Sanford walked the Appalachian Trail all the way to Argentina, and the golf achievements of Tiger Woods, the "insatiable links lecher" (the New York Post's words), suddenly seemed even more impressive, considering the other claims on his energies.

Pope Benedict XVI said scientific tests "seem to conclude" that bones found in a sarcophagus under a Rome basilica were those of the apostle Paul. The remains of a Union or Confederate Civil War soldier were buried with honors after being unearthed at a construction site in Franklin, Tenn., site of an 1864 battle that produced 9,000 casualties. Wounded in 1917 at Passchendaele, Harry Patch, Britain's last survivor of the World War I trenches, died at 111. Ray Nance, 94, was the last of the "Bedford boys" from the Virginia town that lost 22 sons in World War II. Millvina Dean, 97, the last of the Titanic's 705 survivors, was 9 weeks old when it sailed.

Perhaps Tsutomu Yamaguchi will survive 2010. Isn't it pretty to think so?

Monday, January 4, 2010

Food Fighter

A profile in The New Yorker of John Mackey, the oddball dreamer who created Whole Foods:

John Mackey, the co-founder and chief executive of Whole Foods Market, refers to the company as his child—not just his creation but the thing on earth whose difficulties or downfall it pains him most to contemplate. He also sees himself as a “daddy” to his fifty-four thousand employees, who are known as “team members,” but they may occasionally consider him to be more like a crazy uncle. To the extent that a child inherits or adopts a parent’s traits, Whole Foods is an embodiment of many of Mackey’s. A Whole Foods store, in some respects, is like Mackey’s mind turned inside out. Certainly, the evolution of the corporation has often traced his own as a man; it has been an incarnation of his dreams and quirks, his contradictions and trespasses, and whatever he happened to be reading and eating, or not eating.

A year ago, Mackey came across a book called “The Engine 2 Diet,” by an Austin, Texas, firefighter and former professional triathlete named Rip Esselstyn. Basically, you eat plants: you are a rabbit with a skillet. Mackey had been a vegetarian for more than thirty years, and a vegan for five, but the Engine 2 book, among others, helped get him to give up vegetable oils, sugar, and pretty much anything processed. He lost fifteen pounds. This thinking about his body dovetailed with a recession that left many shoppers reluctant or unable to spend much money on the fancy or well-sourced food that had been the stores’ mainstay. Mackey, in a stroke of corporate transubstantiation, declared that Whole Foods would go on a diet, too. It would focus on stripped-down healthy eating. Fewer organic potato chips, more actual potatoes. He told the Wall Street Journal in August, “We sell a bunch of junk.”

The repudiation was rash, since Whole Foods would still be selling junk, of a kind. Mackey, an unrepentant foot-in-mouther, as often a fount of exasperation as of inspiration, tried to explain that his comment had been misunderstood. Mackey has been bewildered by the way some things that he has said or done have brought trouble on him and Whole Foods. Public opinion can be capricious and—when you’re a grocer, a retail brand, and a publicly traded company—hard to ignore or override. "It's the Jihad"

Islamic terrorism is an especially vulnerable point for the politically-minded and politically correct Obama administration, and, as explained in The Telegraph, they seem to know this:

Complacency, faux moralising and partisan shots at Republicans. It was a neat summary of where Obama is going wrong after the Christmas Day debacle when the Nigerian knicker bomber managed to waltz onto a Detroit-bound flight.

For a man who campaigned denouncing the politicisation of national security under President George W Bush, it is worth noting how intensely political Obama's treatment of what might henceforth be known as Underpantsgate has been.

His White House recognised its political vulnerability more readily than it comprehended the level of danger faced by Americans.

Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab's father had courageously contacted the American Embassy in Abuja in November and met the CIA station chief to tell him that his son was involved with fundamentalist elements in Yemen. American intelligence had also intercepted discussions in Yemen about a possible attack by "the Nigerian".

The Obama administration knew most, if not all, of this by last Sunday, 48 hours after the attack was thwarted. But the priority in Obamaland was to play things down and take pot shots at the Bush administration.

Janet Napolitano, the Homeland Security chief – who prefers the term "man-caused disasters" to "terrorism" - blithely stated that there was "no indication that it is part of anything larger". She then insisted that the "system is working".

Although Napolitano has taken a lot of flak for these comic utterances, she was not "misspeaking" but trotting out the agreed talking points of the day.

Robert Gibbs, Obama's chief mouthpiece, also stated that "in many ways this system has worked" and would say nothing about a possible wider plot.

In Hawaii, where Obama was holidaying, Gibbs's deputy Bill Burton told the press that "we are winding down a war in Iraq that took our eye off of the terrorists that attacked us" and that Obama was reviewing "procedures that have been in place the last several years" (i.e. Bush instituted them). He added, without apparent irony, that "the President refuses to play politics with these issues".

Meanwhile, the White House was working overtime to build a case against Bush. A source in the White House counsel's office told The American Spectator of memos frantically seeking information that would "show that the Bush Administration had had far worse missteps than we ever could".

Republicans smell blood. There is a pattern in the Obama administration of dismissing Islamist terrorist attacks as regrettable random acts. In his radio address after Major Nidal Hassan's slaughtered 13 at Fort Hood, Texas, Obama made no mention of terrorism or militant Islam, instead blandly promising that the "ongoing investigation into this terrible tragedy" would "look at the motives of the alleged gunman".

Hassan was a committed Islamist who had corresponded with the fanatical Yemeni imam Anwar al-Awlaki. In June, Abdul Hakim Mujahid Muhammad, a Muslim convert being watched by the FBI and who had previously travelled to Yemen, murdered a US Army recruit in Arkansas. That rated only a tepid statement by Obama about a "senseless act of violence".

But the violence wasn't senseless, it had a calculated objective - just as Abdulmutallab was not, as Obama described him, an "isolated extremist". No wonder many Americans want to grab Obama by the lapels and scream: "It's the Jihad, stupid."

Meanwhile, the White House was working overtime to build a case against Bush. A source in the White House counsel's office told The American Spectator of memos frantically seeking information that would "show that the Bush Administration had had far worse missteps than we ever could".

Republicans smell blood. There is a pattern in the Obama administration of dismissing Islamist terrorist attacks as regrettable random acts. In his radio address after Major Nidal Hassan's slaughtered 13 at Fort Hood, Texas, Obama made no mention of terrorism or militant Islam, instead blandly promising that the "ongoing investigation into this terrible tragedy" would "look at the motives of the alleged gunman".

Hassan was a committed Islamist who had corresponded with the fanatical Yemeni imam Anwar al-Awlaki. In June, Abdul Hakim Mujahid Muhammad, a Muslim convert being watched by the FBI and who had previously travelled to Yemen, murdered a US Army recruit in Arkansas. That rated only a tepid statement by Obama about a "senseless act of violence".

But the violence wasn't senseless, it had a calculated objective - just as Abdulmutallab was not, as Obama described him, an "isolated extremist". No wonder many Americans want to grab Obama by the lapels and scream: "It's the Jihad, stupid."

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Dissertations on dudeness

The power of academia is that everything can be the object of study, and that includes cult movies like "The Big Lebowski", as reported here in The New York Times:

Mr. Eco certainly seemed to presage the existence of “The Big Lebowski” when he wrote in his essay about “Casablanca” that a cult movie must be “ramshackle, rickety, unhinged in itself.” He explained: “Only an unhinged movie survives as a disconnected series of images, of peaks, of visual icebergs. It should display not one central idea but many. It should not reveal a coherent philosophy of composition. It must live on, and because of, its glorious ricketiness.”

The glue that holds “The Big Lebowski” together, as gloriously rickety as it is, is Mr. Bridges’s performance. Pauline Kael once observed that Mr. Bridges, who is gathering Oscar buzz this month for his performance as a down-on-his-luck country singer in “Crazy Heart,” “may be the most natural and least self-conscious screen actor that has ever lived.”

In an essay in “The Year’s Work in Lebowski Studies,” Thomas B. Byers — he is a professor of English at the University of Louisville — points out that more mainstream actors like Harrison Ford or Kevin Costner or Tom Hanks could not have pulled off the role of the Dude. “What makes Bridges less of a star is precisely what makes him perfect for ‘Lebowski,’ whose particular niche of success depends on its outsider, cult status,” Mr. Byers writes.

As a new generation of “Lebowski” fans emerges, Dude Studies may linger for a while. In another of this book’s essays, “Professor Dude: An Inquiry Into the Appeal of His Dudeness for Contemporary College Students,” a bearded, longhaired and rather Dude-like associate professor of English at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., named Richard Gaughran asks this question about his students: “What is it that they see in the Dude that they find so desirable?”

One of Mr. Gaughran’s students came up with this summary, and it’s somehow appropriate for an end-of-the-year reckoning: “He doesn’t stand for what everybody thinks he should stand for, but he has his values. He just does it. He lives in a very disjointed society, but he’s gonna take things as they come, he’s gonna care about his friends, he’s gonna go to somebody’s recital, and that’s it. That’s how you respond.”

Happy New Year, Dude.

The ego in our lattes

Has Starbucks turned America's middle class into status-seeking hypocrites? That's the claim in Bryant Simon's new book, "Everything but the Coffee", as you can read in this review in In These Times. Crazy me, I thought it was all about getting a great cup of coffee.

Simon shows us how we really live, and it ain’t pretty. There was a time, not so long ago, Simon reminds us, that many of us wondered why people would pay so much money for a cup of coffee—even as we were edging closer in line to place our own order. Starbucks, writes Simon, “had little to do with coffee, and everything to do with style, status, identity and aspiration. … Starbucks delivered more than a stiff shot of caffeine. It pinpointed, packaged, and made easily available, if only through smoke and mirrors, the things that the broad American middle class wanted and thought it needed to make its public and private lives better.” Starbucks fed our emotional needs for status. It became our little “self-gift,” an emotional pick-me-up. It allowed us to feel successful.

It also provided a safe, clean “third space” between home and work, those big chairs and couches becoming our new public sphere. It brought us exotic places and sounds, exposed us to an underground in the safety of a cushy seat: teaching us about places where our coffee came from, and new music and literary voices. It tried to be our cultural guide and helped us feel good about our environmental footprint through its green campaigns and aid to farmers, even if Starbucks did little and we did nothing but buy coffee. It did so consciously, purposefully manipulating our desires, hopes and aspirations, all the while making us feel good about ordering up a venti soy latte.

But, we also knew, on some level, that it was all a delusion we actively participated in. “Starbucks worked as a simulacrum,” Simon writes, “it stamped out the real essence of the original idea of the coffee house and, through proliferation and endless insistence, became itself the real thing for many bobo and creative types.” Even as we believed we were being individuals, demonstrating our sense of style, we were just following the javaman’s master plan. In seeing Starbucks as a third space, as a solution to the environment and globalization, we played into the illusion and lost ground on these fronts.

Saturday, January 2, 2010

Friday, January 1, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)